Many on the left hoped that the silver lining of the prolonged slump since the Great Recession of 2008 would be to discredit capitalism and build momentum for drastic change. Only the youngest voters have stayed wedded to this idea, with much of the broader electorate holding a fairly positive view of the status quo: 76 percent of voters rate economic conditions as either “very good” or “somewhat good,” according to a CNN poll in late December.

For liberals, this sets up a worrisome political dynamic ahead of 2020. Typically, positive attitudes about the economy are good news for incumbent presidents.

But one nice thing about a strong labor market is that it creates political space to finally pay attention to the myriad social problems that can’t be solved by a “good economy” alone — things like child care, health care, college costs, and environmental protection — that during, the Obama years, tended to be crowded out by a jobs-first mentality.

Good times, in other words, could be the perfect opportunity to finally tackle the many long-lingering problems for which progressives actually have solutions and about which conservatives would rather not talk.

For years, there was a mostly true narrative that despite positive GDP growth, actual good economic news was largely limited to stock prices and corporate profits. More recently, however, the corner has turned.

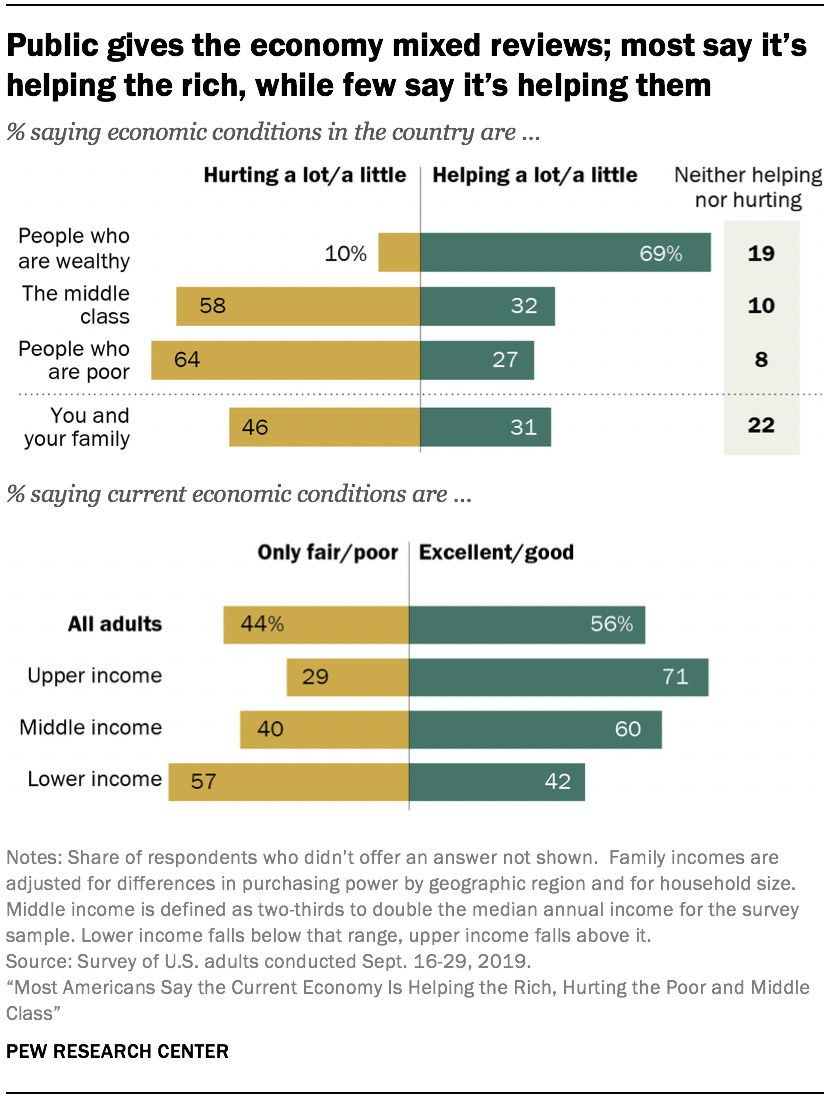

The Bloomberg Consumer Comfort Index shows a high degree of optimism about the future of the economy. A Gallup poll found that 65 percent of adults think it’s a good time to find a quality job, and 55 percent rate economic conditions as either good or excellent. Fifty-six percent of Americans rate their personal financial situation as good or excellent, 66 percent say they have enough wealth and income to live comfortably, and 57 percent say their personal financial situation is improving.

Corporate profits, meanwhile, remain high but have actually been falling as a share of the economy since 2012.

At the same time, a low unemployment rate plus higher minimum wages in many states mean that pay is rising — especially for workers at the bottom end.

At the same time, according to voters, “the economy” no longer rates among the top four problems facing the nation.

That doesn’t change the fact that macroeconomic management remains, substantively speaking, one of the government’s most important tasks. But the mission for the next administration won’t be to heal a broken labor market, but to take advantage of a sound one to create huge benefits.

One nice thing about low unemployment is that it tends to lead to wage increases.

Employers, of course, don’t like to raise wages when they can get away with it. But in the context of a strong labor market, that stinginess brings its own benefits, since the only way to get away with avoiding big wage increases is to take a risk on workers who might otherwise be locked out. Companies have suddenly found themselves more open to hiring ex-convicts, for example, which is not only good for a very vulnerable population but also makes it much less likely that ex-offenders will end up committing new crimes. Similarly, people in recovery from drug and alcohol addiction aren’t normally an employer’s first choice of job applicants. But beggars can’t be choosers, and a strong labor market is a great chance for people who need of a second chance to get one.

A related issue is racial discrimination. For as long as we have records, the black unemployment rate has always been higher than the white unemployment rate. But the racial unemployment gap, which surged during the Great Recession, has been steadily narrowing ever since. Discrimination becomes more costly during periods of full employment, and continued strength in the labor market will continue to whittle away at this and other similar gaps.

Last, but by no means least, a strong labor market is the optimal time for labor militancy.

The threat of a strike is much more potent at a time when customers are plentiful but potential replacement workers are scarce. And periods in which it’s relatively easy for an experienced worker to get a new job with a new company are typically periods in which it’s hard for employers to intimidate workers out of organizing. Indeed, as Polish economist Michael Kalecki predicted way back in 1943, this is one reason why business interests somewhat counterintuitively fail to advocate for robust full employment policies. An actual recession is bad for almost everyone — but a healthy chunk of the population out of work makes for a decent disciplinary tool, and it keeps the political agenda occupied with things like the need to fix the mythical “skills gap” rather than with worker demands for a bigger piece of the pie.

Meanwhile, a reduced public obsession with the need to address short-term economic problems opens up more space to address the many longstanding problems that can’t be cured by a strong economy.

Even as the labor market has gotten steadily healthier in recent years, the American birth rate continues to fall from its recession-era highs.

Women tell pollsters that’s not because the number of kids they’d ideally like to have has fallen. Instead, the No. 1 most-cited reason is the high cost of child care. Child care doesn’t get more affordable just because the unemployment rate is low. If anything, it’s the opposite — child care is extremely labor-intensive, and the prospects for introducing labor-saving technology into the mix look bad. To make child care broadly affordable would require government action; it’s just not going to happen in a free market, which doesn’t magically allocate extra income to people who have young kids.

More broadly, America’s sky-high child poverty rate compared with peer countries is entirely attributable to our failure to enact a child allowance policy. A better labor market helps marginally, but it doesn’t address the fundamental issue that a new baby increases financial needs while also making it harder to work long hours.

By the same token, getting sick is expensive, and simultaneously, often leads to income loss. Absent a strong government role, there’s no way to ensure that care and other needed resources are there for those who need it most.

Last, but by no means least, there’s the environment. An unregulated economy generates a lot of pollution, and nothing about strong economic growth changes that. On the contrary, what happens is the long-term negative impacts of the pollution end up outweighing the short-term benefit of letting businesses operate unimpeded. Moving the ball forward on everything from climate change to lead cleanup to air pollution requires persuading voters to make the opposite calculation: that the economy is doing well enough to prioritize long-term concerns.

These are all policy areas in which progressives want to act regardless of the current state of the economy. But the mass public is more likely to give these ideas a hearing when there’s no real worry of a short-term economic emergency. And conservatives really have nothing to say about any of them.

The administration of President Donald Trump is steadily pursuing a policy agenda aimed at stripping as many people as possible of their health insurance, but the president never talks about it.

By the same token, his reelection campaign claims “we have the cleanest air on record” when, in fact, air quality has been declining under Trump, and his administration is working on a bunch of regulatory rollbacks that will make air pollution even worse. Meanwhile, Trump’s only child care proposal has been the idea of creating a one-off grant program designed to give states extra money if they agreed to lower quality standards for child care settings.

Progressives have ideas about how to boost economic growth, but conservatives have their own clearly articulated vision, one centered on tax cuts and business-friendly regulation. By contrast, when it comes to other social concerns that transcend the short-term state of the economy, progressives have a set of proposals and, well, conservatives have basically nothing. The strong economy is, itself, an asset for Trump during his reelection bid. But the recovery he’s presiding over plainly began under former President Barack Obama, and all Trump has really done is avoid rocking the boat too much. Meanwhile, growth itself is raising the salience of a whole range of other topics on which conservatives have essentially nothing to say.

Democrats’ best path forward isn’t in denying that economic progress has been made, but in emphasizing the extent to which it’s absurd that a rich and stable country like ours is also home to sky-high child poverty, middle-class families who can’t afford day care for their kids, and worsening air quality. Low unemployment is great, but it should be the start of good social policy — not the end.

Help

Help